#NCCRWomen Campaign

About the Campaign

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of women obtaining the right to vote in Switzerland, the NCCRs introduce you to some women working in Swiss research institutes.

Meet the NCCR women - follow #NCCRWomen on YouTube, Instagram and Twitter or check out the portraits of the NCCR RNA & Disease women below!

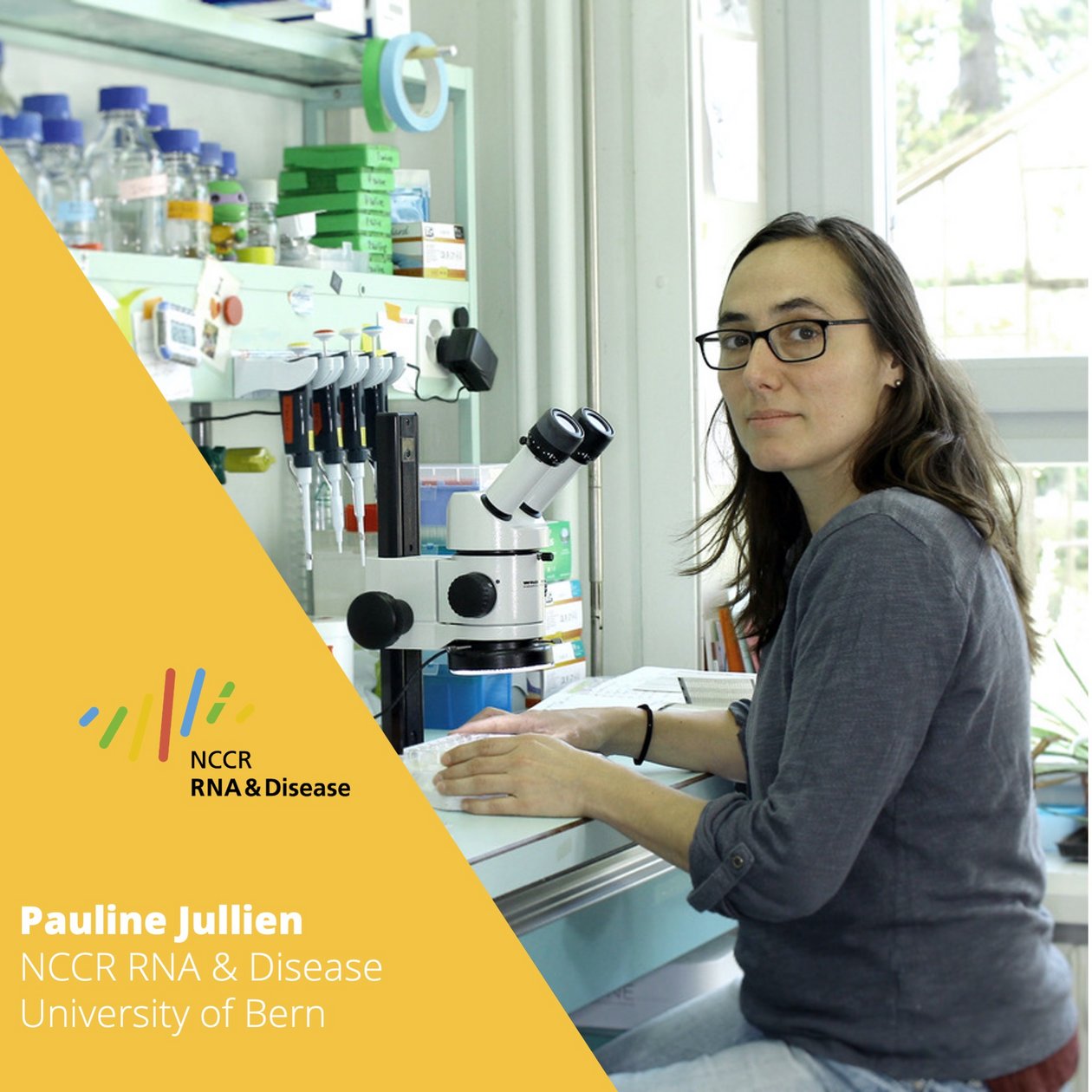

Pauline Jullien studied Biology at the University of Grenoble and obtained her PhD from Tübingen. Following her PhD, she conducted research as a postdoctoral fellow at the Temasek Life Sciences Laboratory in Singapore. Upon returning to Europe, she did a second postdoc at ETH Zurich. Currently, she holds the position of assistant professor at the University of Bern, where her lab focuses on understanding how epigenetic marks are transmitted from one generation to the next in plants.

Pauline, what inspired you to become a scientist?

I think it all started with my dad. My father was a farmer who was very interested in the nature around him. He was very good at solving problems and fixing things. I spent a lot of my childhood outdoors with him, and that probably forged my interest in understanding nature and solving problems. From an early age, I was better at science than other subjects. When I was about 13 years old, I wanted to be an astronaut. In the library of my secondary school there were cards describing the educational paths for different careers. But there was no card for astronauts, so I called the European Space Agency (ESA), which told me that I had two options: either join the military to become a pilot or become a scientist. Considering my physical attributes – I am quite short and wear glasses - I chose the second option.

… and how did you get started in the field of plant epigenetics?

It happened during my ERASMUS year in England. I was searching for a laboratory in France to do my Master's degree and one of the group leaders I approached was Frederic Berger. He was visiting someone in Cambridge at that time and agreed to meet me. We had a conversation lasting more than two hours, during which he passionately explained to me all about seed development and epigenetics. Although I felt a little lost during the conversation, his enthusiasm and knowledge were contagious. He even invited me for a coffee and some chocolates, which sealed the deal. We ended up working together for more than seven years on two continents.

What inspired you to pursue a scientific career?

Apart from the astronaut story, I'm not sure there was one particular thing that definitively inspired me. Ultimately, I think it's my addiction to problem solving, my curiosity, and my love of learning new things that got me to where I am now. I wanted, and still want, to understand how things work and I am fascinated by it. How a genome can be orchestrated to give all the different cells of an organism as well as change depending on environmental cues? That’s just amazing. No?

What are some of the most rewarding aspects of being a scientist?

One of the most rewarding aspects of being a scientist, in my opinion, is when we get new results that challenge our thinking and force us to come up with new hypotheses or models. It is incredibly satisfying when the pieces of the puzzle start to come together. I love that feeling. Additionally, teaching is another rewarding aspect for me: being able to share knowledge and watching students evolve and grow as scientists during their time in the lab.

What does a typical day look like for you?

A typical day for me starts at 6:30 a.m. I begin by preparing my three children for school and daycare, ensuring they are ready and good for the day. Then I head to the train station and commute to work. At work, I meet with the members of my lab. We discuss new results and plan future experiments. If I have no other meetings or teaching, I spend the remaining time on tasks like analyzing data, writing, reading literature or reviewing grants or papers.

What do you like most and least about it?

What I enjoy the most about my day on the professional side is the scientific discussions and exchanging ideas with the people of my lab. On the personal side, I like the evenings spent with my children when they share stories about their day. What I like the least is the stress of rushing around, commuting and worrying about not being on time.

Can you tell me more about your research - what is the main question you try to answer?

Our primary focus is to understand the mechanisms allowing the robust transmission of epigenetic information from one generation to the next. Additionally, we have recently started to also study the plasticity of epigenetic information. We are investigating how external factors, like infection by pathogens, can induce modifications in the epigenome. By looking at both the transmission and plasticity of epigenetic information, we hope to gain a better understanding of how plants adapt and respond to their environment.

What are some of the most exciting scientific discoveries or breakthroughs that you have been a part of?

During my PhD and first PostDoc in Singapore, our work together with the work of a few other labs in the world discovered how imprinted* genes are regulated during plant reproduction. Although we were working on specific genes at the time, these studies shed light on the complexity of epigenetic regulation occurring during plant reproduction. It was a very exciting time also because we had a lot of interactions with people working on genomic imprinting in mammals, finding commonalities and differences.

(*Imprinting: Imprinting refers to the silencing of a specific gene, while the gene from the other parent is expressed. The mechanisms underlying imprinting are not yet fully understood, but they involve epigenetic modifications that are erased and subsequently reestablished during the formation of eggs and sperm.)

What are some of the most promising areas of research in your field today, and how do you see this field evolving in the future?

I can imagine two directions in which plant molecular research can move to. So far, most plant molecular and genetic research was done on model plants in controlled growth conditions. With recent technological advances, we can now open up to many other model organisms and this will tell us how general and conserved all the mechanisms we have previously been working on are. Second, we should study these molecular regulations and pathways under non-controlled conditions that are closer to genuine plant growth conditions, which involve a multitude of factors. This second aspect is likely to take more time due to its complexity, but also due to the restrictions of the current GMO legislation.

What would you like to say to your younger self about a scientific career?

Go for it and enjoy it as long as possible!

How do you balance your work as a scientist with your personal life, and what strategies have you found to be effective for maintaining “work-life balance”?

To be honest, I find this very difficult. Not so much on a day-to-day basis, it is hard but there the key is compartmentalization. My partner and I are very organized, and we have a Google calendar containing all our imperatives for work and for the children. What I find more difficult is planning the future. Currently, I am in a non-tenure track professorship, which means that I need to actively search for my next position. The dilemma comes from the fact that what may be the best career move for me might not necessarily be what is best for my family, and vice versa. This dilemma is daunting.

Where do you find inspiration?

For my own research, most of my inspiration and ideas come after a day of writing or analyzing data when I let my mind wander on my way home. In terms of general biological questions, since I am a plant biologist, I look at the plants outside and wonder how things work - whether this may relate to the molecular mechanism I am studying; whether it is known or not …

What do you like to do outside the lab?

I really like to have quality time with my children, like reading or doing an activity together. I also like hands-on activities like gardening or DIY projects. My partner and I have been renovating a house in our spare time for the last 2 years. It is quite slow and messy but also very rewarding. We have learned a lot, from gluing parquet to electricity and solving problems one after the other. I find doing manual activities very relaxing.

Do you think the scientific community would be different if more women were in leading positions?

Definitely! I would not only restrict the diversity issue to women but to many other factors, like big vs. small research groups, with or without family, full vs. part-time work, locals vs. foreigners, applied vs. fundamental research, developing vs. disruptive science, etc. I think the more diverse the environment or community, the healthier it is. Interestingly, the relationship between productivity and diversity has been well studied by ecologists - maybe we could adopt some of their findings.

And finally, what do you think would help make a career in science more attractive for women?

I can only speak about my own experience. I never felt that I couldn’t do it just because I am a woman. But as a mother of three children, what might make me leave science eventually is my family. I think that making the scientific career more compatible with family life is crucial. This includes various aspects such as childcare and maternity support, but also more important factors such as job security and mobility, which are factors not easy to tackle for parents who want to stay in basic research.

Anne completed her studies in Chemical Engineering at the University of Applied Science in Darmstadt and pursued further studies in Biochemistry at the Université Pierre et Marie Curie in Paris. She then went on to conduct her doctoral research at the Max-Planck-Institute for Biochemistry in Martinsried. Following her PhD, she undertook a postdoctoral position at the University of California in Berkeley, USA, funded by an EMBO long-term fellowship and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI). In 1999, Anne became an independent group leader at the Friedrich Miescher Laboratory of the Max Planck Society in Tübingen. Since 2005, she is holding the position of professor of Biochemistry at the Biozentrum of the University of Basel. Her research focuses on studying the organization and localization of protein and mRNA molecules within cells.

Anne, can you tell us how your typical day looks like?

When I get to the lab, I have my first coffee and talk to people in my group to catch up. Then I go back to my office and work. I think about science, write manuscripts, read papers, sometimes discuss with other colleagues or someone comes in and we discuss science. I have an open-door policy, which means that people can come in basically anytime, unless I'm in a meeting. I still have a bench in my lab and I try to do some experiments from time to time. Committees and other meetings can also take up a lot of my days. Other than that, I also travel to a lot of conferences. So, it's really about either communicating or talking about science, thinking about science or reading about science.

What do you do in your free time? Where do you get your inspiration?

I like to paint. I love art. I do sports - I have always done a lot of sports like running, spinning, Pilates or yoga. I like to go out in nature, either hiking, snowshoeing or skiing. And I like to cook - I love good food. Actually, if I hadn’t gotten to this point in my career, I probably would have opened a restaurant with some kind of fusion cuisine, a bit of French, a bit of Italian, but also Japanese style. I sometimes thought about what the menu could look like.

You are an established professor at the University of Basel. Have there been any challenges or obstacles in your academic career that you think are due to the fact that you are a woman?

I don’t think my gender played a role in my training and I didn’t feel disadvantaged until I became a junior group leader. But after I got the junior group leader position in the Max Planck Society, I went for a coffee with someone who was an internal candidate for the position I got. He said that I only got the position because I was a woman. When I confronted the head of the committee with this, he said neither yes nor no. So, I was dismayed naturally. It was a shock to me. I was not aware that gender could be a decisive factor at all and I always thought I got the position because of my scientific achievements, which were quite good.

What is your strategy to deal with such instances?

I just decided that I did deserve this position. No matter what that internal candidate said, he may have deserved it as well, I don’t know. I wanted to prove that I deserved this. Sometimes men say they find me “aggressive”, but I just don’t give up and I stand up for what I think.

Generally, I think it is a fine balance that needs to be kept, on the one hand to say that there is still a lot to do to achieve gender equality and on the other hand not falling into this mantra of always saying that we are disadvantaged. The more we say women are disadvantaged, the more women feel disadvantaged. But we are strong.

Since you started as an independent group leader, have you noticed any changes happening in that respective?

Yes, I do think changes are happening. I think one of the major changes that has taken place, in particular in Switzerland and Germany, where women were often not supposed to work, is that it is now very acceptable to put your child in day-care. And that allows women to take other positions.

Another thing that I also notice from the people in my lab is that men are taking a lot more responsibility in parenting. In my generation, most of my male colleagues have a partner who is not or no longer in science and takes care of the family. Of course, I also have friends who both work in science, but by and large the woman takes care of the family so that the man can take care of his career. So, I think there are some improvements. But for changes in the scientific world, the society has to change.

So, these are improvements in the reconciliation of career and family – do you see also changes happening in how women are perceived? What needs to be changed so that women are treated equally to men?

This is actually much, much harder to change. Because I think there are some intrinsic differences in the way we think about things. I cannot understand a man all the time and men can probably not understand women all the time, right? But one should not pretend that there are no differences in how people think. I don't have a really good solution for this, but my hope is that as it becomes more common to have women in the higher position, we learn to live with different mindsets. Like in international environments. You have a lot of cultural differences in people from different countries. You need to be open, understand that there are differences and learn to accept them. There are hundreds of studies saying that a mixed team is better than homogeneous teams. And in science you want to have the international exchange and be exposed to different cultures and mindsets. This is how we advance.

Do you think that scientific community would change if more women are getting into the leadership positions, e.g., as directors of institutes?

Obviously, because the leadership style is very different. And I think that these women who take this up are actually very brave, because the measure is still the “male way” of leading. But there are very successful examples, like Maria Leptin or Fiona Watt, who are changing the environment.

I think that there's an incentive to get the women into these positions. Still, we need to be careful that, as so often, women are not over-burdened and don't feel pressured to take up these positions.

A similar problem seems to be that women are frequently required to participate in a high number of committees for the purpose of gender representation, which can be particularly challenging for women starting their own research groups. What do you think about this?

I think this is really an issue. There are two things you raised in this context. First, of course, we need to have an adequate representation of women in all committees, but that means that because fewer women actually have a position, women have more assignments than men. Of course, there are also men who are very engaged. But basically, women usually have more tasks than the men.

Secondly - and this is also very often true for men - it is often very difficult for assistant professors, especially in the case of tenure-track, to say "no" to such requests because they don't know how it might ultimately affect their tenure decision. At the end of the day, if you have published well, then there should not be an issue. However, in the tenure-track assessment other things are also taken into account, for example how engaged the person is or how integrated the person is in the community, etc.; I think that the directors and the people who make the tenure-track decision have the responsibility to protect the assistant professors from feeling obliged to be part of too many of these activities and to allow them to focus on setting up a lab, which is stressful enough.

What challenges did you encounter when you started your own lab?

When I started my group, I had people that perhaps I shouldn't have hired in the first place. I made the mistake of thinking that all the students I hired would be as excited about the projects as I was.

Also, I was relatively young and the students I hired were not much younger than me. We were basically of the same age group and we also hang out a lot. At some point, I think we were almost more friends than I was the boss. This led to some conflicts and my group almost fell apart, which made me feel inadequate and stupid. It helped when I confided in an older group leader I had known for a long time.

Today, everyone talks about “role models” or “mentors”. Did you have role models or mentors who influenced your scientific career, and do you think it is important to have role models?

I never really thought about this, I have to say. I think I just wanted to do science. So, it was not so important to me. As I said, I was talking to this senior group leader that I knew for a long time. He was basically mentoring me, but I wasn’t seeking for any formal mentorship back then. I also never thought I wanted to be like for example Marie Curie. I just want to do science. This was what I wanted to do.

Do women approach you for mentorship? Can you help them find their way in their careers?

Yes, people come and seek advice. I try to listen, because everybody has their own way. I think the most important thing is to be honest with yourself and know yourself - we have all strengths and weaknesses and it is very useful to know them and act on them. You can strengthen your weaknesses, but at the end of the day, you will still be the person you are. I advise people to think about what they really want in life and for themselves. And how much they're willing to give for it.

The primary goal in our profession should be that you are really driven and think that this is the best thing you can do in your life. And then, of course, you cannot have that sharp boundary like in a nine-to-five job. I'm not saying you shouldn't turn off your thoughts. You have to empty your mind and should of course have another life as well. But if you have this nine-to-five idea, then you need to rethink whether this job is really what you want.

What do you think would make a scientific career more attractive to women?

I think that there is some room for improvement in childcare, perhaps with more flexible opening hours at daycare. But at the level of research institutes, I think that promoting dual-career opportunities would really help. It's always difficult when two people need positions in the same place. Often, the assumption is that in dual-career opportunities the man is higher qualified and it is about finding a job for his wife or partner; basically, trying to do the less qualified woman a favor to get a position that she doesn’t deserve. But this is not what I mean. In my experience, we often want to hire the woman and then face the challenge of finding an opportunity for the partner. There, one should be more creative in finding solutions. For example, creating positions for the partners that act as incubators for their development until they can secure their own positions.

One should also explore opportunities in other institutes in Switzerland that might be better suited for a partner’s position in order to provide the best environment. For example, one could negotiate to pay that person’s salary if another institute provides lab space. I wish that there was a more communal sense facilitating such things and researchers becoming more open to making such things happen. There's a lot of room for improvement in that direction. Ultimately, there needs to be a bigger picture, because in the long run, everybody's going to benefit from this.

(Interview conducted on April 5, 2023 by V. Herzog)

---

We are sharing profiles of women researchers of the NCCR RNA & Disease as part of the #NCCRWomen campaign. You can find out more about the campaign on YouTube, Twitter or Instagram.

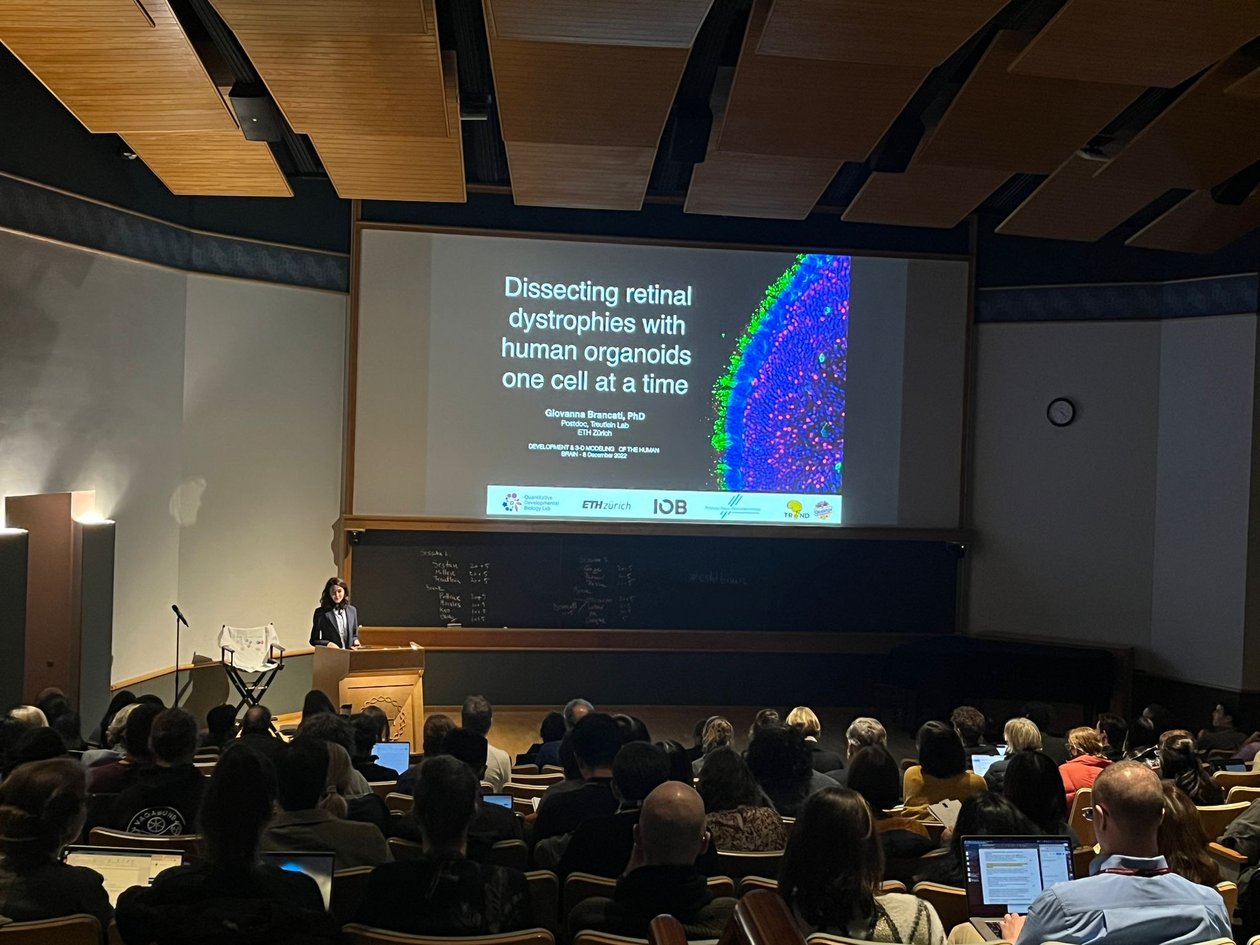

Giovanna is originally from Palermo, Italy, where she completed her Bachelor's degree in Biotechnology after a research internship at Rice University, Houston. She earned her Master's degree at the University of Bologna and conducted her Master's thesis at EMBL Grenoble. She then moved to Basel to do her PhD at the Friedrich Miescher Institute (FMI), where she worked in the lab of Helge Grosshans and was part of the NCCR RNA & Disease. She then moved to the Institute of Ophthalmology Basel and ETH Zurich as a postdoctoral researcher. Currently, Giovanna is a scientist at Roche's newly founded Institute of Human Biology (IHB), where she develops innovative 3D cell culture models for retinal diseases.

What inspired you to become a life scientist, and how did you get started in this field?

During high school I was studying lots of literature and I thought I would become a professor or an archeologist. Then I attended a university orientation week, and learned about viruses, gene therapy, and biotechnology. It was serendipitous and eye opening! In addition, the support of my (female) math teacher was essential to give me the confidence to consider a career in science.

What inspired you to pursue a graduate degree in life sciences?

I chose to do a PhD in life science because I wanted to build a solid scientific and professional foundation for a career in biomedical research. Also, I loved working in the lab - and I still do!

What are some of the most rewarding aspects in research?

By far the most rewarding aspects are firstly the training of young students - there is something magic in observing their scientific development – and secondly that one joyful moment when I observe the results of a successful experiment.

What does a typical day look like for you?

I do not really have a typical day, every day is somehow a unique combination of experiments, meetings with colleagues to plan and discuss new - or failed! - experiments. I also invest time in building relationships with colleagues at work, going for lunch together or on short breaks. Over time, many colleagues became some of my best friends and meeting them fills me with joy.

What is the main question that your research tries to answer?

I am currently building new and innovative 3D cell culture models to study blinding diseases and help find novel treatments. I am particularly fond of retina organoids because, firstly, I strongly believe that they will become an invaluable in vitro tool to help identify novel treatments for blinding disease for which treatments are scarce, and secondly, they are beautiful!

What have been some of the benefits and challenges of working in a collaborative environment?

Collaborating with many people has the clear advantage of pushing research forward in a much faster way. During my PhD and postdoc time, I have been part of many different collaborative teams, and it is fun! Different personalities and expertise blend with each other to reach a common goal - this is motivating and fascinating. Of course, there are challenges associated to big teams, every person comes with their own personality and personal interests. But I believe that continuous clear and transparent communication about goals and expectations is key to the success of the team.

How do you stay motivated and overcome obstacles when conducting scientific research?

I have a strong sense of purpose. I strongly believe in what I do, and why I do it. Obstacles and setbacks can be annoying, also somewhat painful, but there’s lots to learn from them. I always try to keep a positive attitude. Everything can be fixed, and if not, I will find a way around it. Also, I have a fantastic support group, family, friends and mentors, who help me “recharge”.

How do you balance your work as a scientist with your personal life? What strategies have you found to be effective for maintaining “work-life balance”?

This is a tough question. Work-life balance is different for every scientist, and there are no one-fits-it-all solutions. To be honest, I am not good at leaving work at work, and this can sometimes be stressful. I enjoy my work and there is always something more I can do in a day, but I learned to set up boundaries and plan time to do things that I like, e.g., doing sport, meeting friends, traveling, or anything that allows me to disconnect. As a coach once told me: “Plan something after work and add it to your calendar, drop your pipettes and get out of the lab when it is time”.

Can you describe some of the challenges you have faced as a woman in science and how you overcame them?

During my PhD, I have been harassed at a conference. It hurt, because I thought the professor was interested in discussing science with me, but obviously he was not. It took time to get over it and restore my confidence. I did not tell anyone, and in hindsight, I should have. Microaggressions happen. Sexual harassment is real. We do not talk about it as much as we should, and it is great to finally see universities slowly taking a stand against it, for example with the “Sexual Harassment Awareness Day”.

Over time, I realized that my way to overcome challenges faced by women in science, is to support other women and pay it forward. I joined groups like TWIST Basel and 500Women Scientists and became an advocate for women in science and gender equality.

Moreover, I think there is still some bias regarding what a scientist should look like. You know, the man with white hair and glasses hidden in a lab. When I was younger, I did not wear makeup or skirts at work because I thought people around me would not take me seriously, because that made me stand out and I wanted to fit in. Later on, when I found the courage to admit this, I realized that many younger colleagues feel the same. So, we started “Skirtfriday”, which is a day in which we wear what makes us feel good. You can be a scientist and wear anything, without worrying about other people’s opinion. So now on Fridays, I always wear skirts.

What advice would you give to young girls who are interested in pursuing a graduate degree or a career in life sciences?

Do it! It is rewarding, interesting and never boring. It opens a lot of unexpected doors!

If you are unsure whether it is for you, reach out to people who are currently studying or have a life science background.

Who has been the biggest role model or mentor in your scientific career, and how have they influenced your work?

I was lucky and had many people who inspired and supported me, and still do! Different people have been instrumental in different moments of my career. For example, I learned a lot from my PhD supervisor Helge Grosshans and postdoc supervisors Gray Camp and Barbara Treutein – the way I do science has been strongly influenced by them. My family, on the other hand, and particularly my nonno (grandfather) have been my constant support and source of motivation.

Have you been able to provide mentorship or support to other young women pursuing careers in life sciences, and if yes, what have you learned from these experiences?

All my mentors told me that they found joy in helping young people develop. I never fully understood it, until I felt that joy myself. I did not ask to become someone’s mentor, but I discovered that some of the younger women in my circle were looking up to me and asking for advice. So, I realized that mentors do not have to be official, we can all be mentors and role models for people around us.

How important do you think mentorship is in helping young women succeed in the scientific community?

I think it is important to help women become more confident. Although the number of women in STEM is increasing, the field is still male-dominated, and mentorship helps navigate it. Sometimes, you need an external point of view, other times you need a strategic advice or simply a sounding board. Mentors can be a precious resource. It takes time to cultivate mentorship relationships, but it is worth it!

What advice would you give to young women who are seeking mentorship or looking for role models in their field of interest?

If you are looking for mentorship, enroll in mentorship programs (for example “Fix the leaky pipeline”). Such programs usually have a framework that helps you find a mentor that fits your needs. Additionally, if you meet someone very inspiring, ask for an informal meeting, like a coffee. People are very happy to meet and share their experience. Do not be worried to get a “no” as an answer and ask. Finally, do not undervalue the support that your peers can give you (Link to iBiology Podcast “What is a Peer Mentoring Group?”)!

Do you think the scientific community was different if more women were in leading positions?

Yes, I strongly believe so. I have worked in laboratories led by both men and women, and I have observed how their leadership style can be different. We need both! And we need equal numbers at the leadership level to set the tone for our institutes. Also, more women in leadership positions will provide role models for younger scientists and help normalize a career in science for all. I think there is truth in the quote: “You can’t be what you can’t see”.

What is your wish for girls studying science in school today?

I wish for them to enjoy science, to choose it and to not allow anyone to make them believe they are not good enough for it. When someone tells you “Girls are not good in science”, be bold and prove them wrong - you are not alone.

---

We are sharing profiles of women researchers of the NCCR RNA & Disease as part of the #NCCRWomen campaign. You can find out more about the campaign on YouTube, Twitter or Instagram.

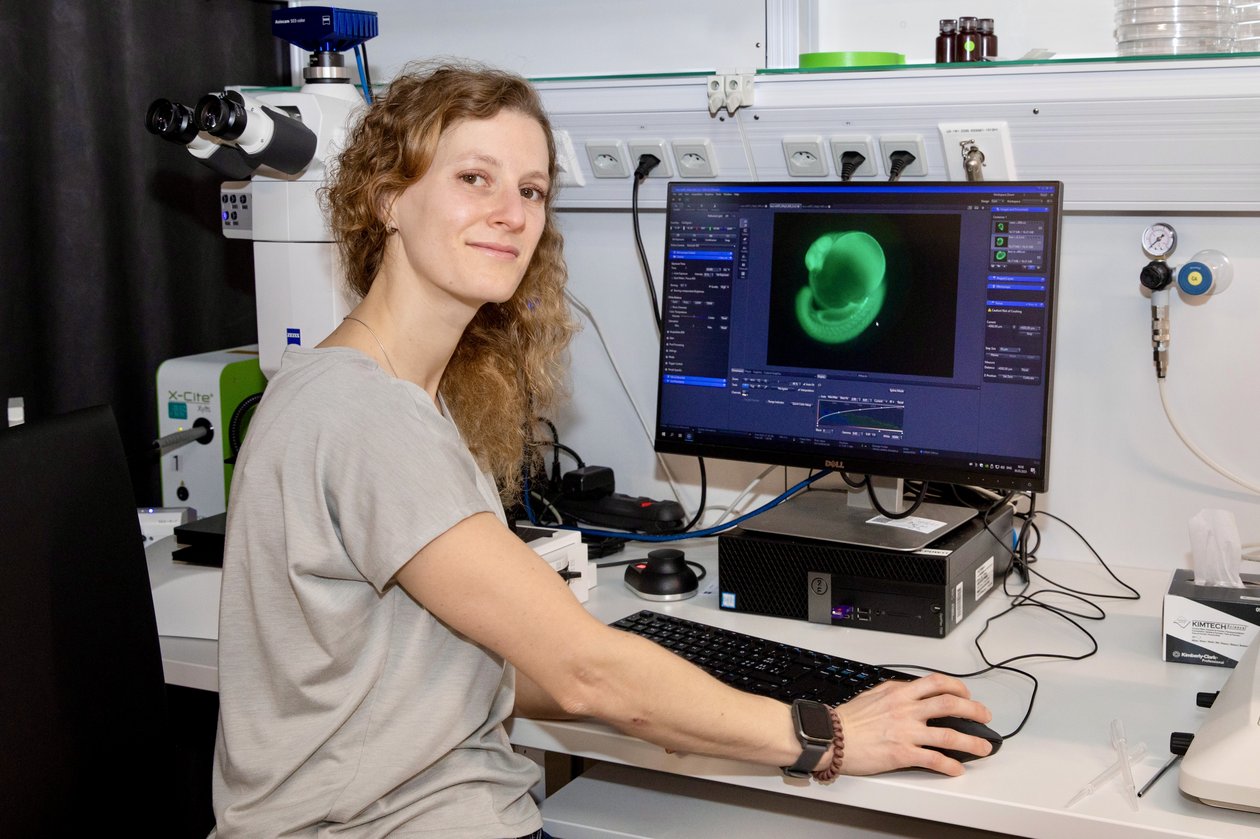

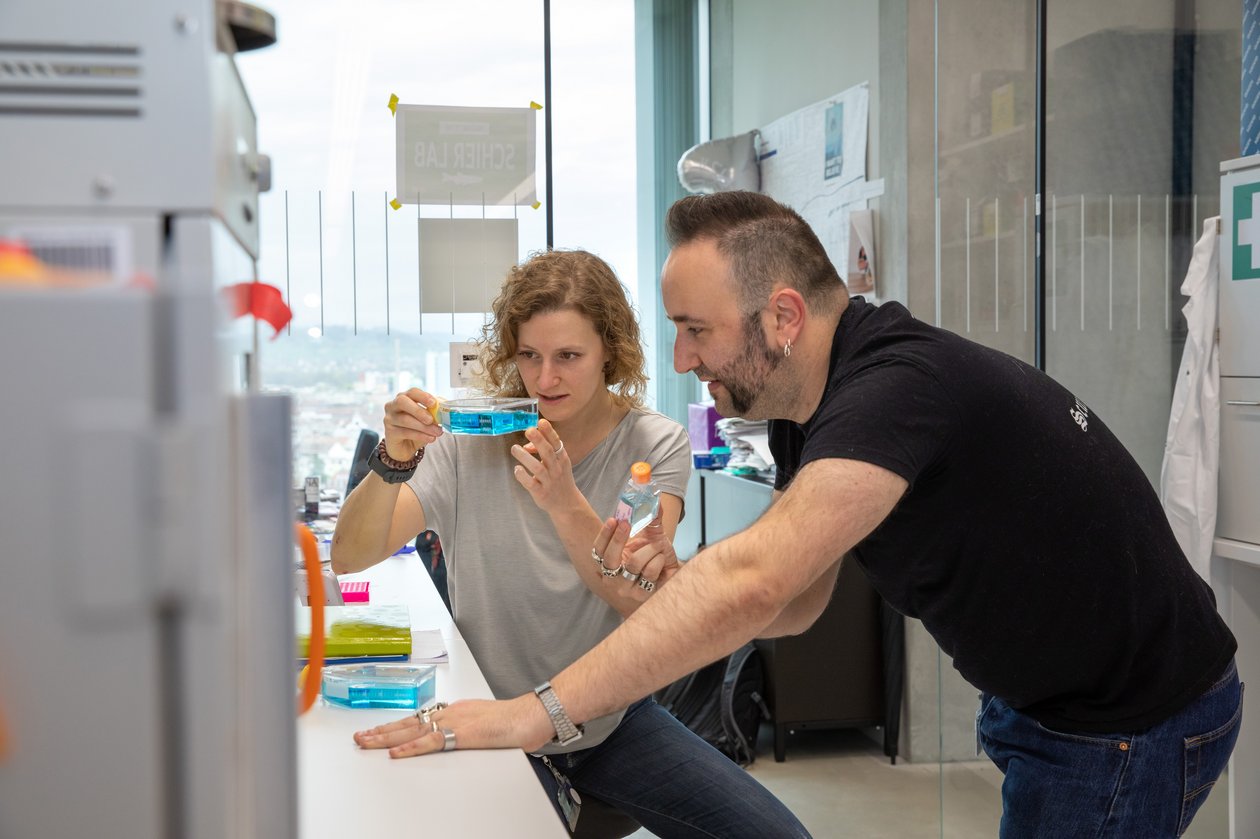

Madalena is originally from Lisbon, Portugal, and earned her undergraduate degree in molecular biology from NOVA School of Science and Technology in Lisbon. She continued her studies with a master's degree at Imperial College in London, before working as a technician in two different labs. Later, she pursued her PhD studies at the Vienna BioCenter. Currently, Madalena works as a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Alex Schier at the Biozentrum in Basel. Her research focuses on how translation control during early embryogenesis contributes to establishing gene expression profiles.

Madalena, how did you become a scientist?

I think the first decision was whether I was going to become a veterinarian or not. But I was very much interested in the research aspect of it. So, I decided to study biology and I thought, I can still transition if I want, but I stuck with biology.

After your master’s degree at Imperial in London, you worked as a research technician in two labs. Why did you choose to do this?

My master's at Imperial was a bit of a rough experience because I was very isolated in the lab. So, I was not sure if the academic path was for me. I stepped back a little and joined two different labs as a technician where I could experience what the actual process of doing research was when being integrated in a group. And after two years, I was convinced that I wanted to follow this career, have more independence and also develop my own project. Working as a technician was probably the best decision that I took to gain experience. It also made the PhD studies much more approachable and enjoyable.

…and then you applied for PhD positions?

When I started to apply for PhD positions, I failed… miserably (laughs). In hindsight, this was great because it opened my perspective. Failure is like a hidden success to direct you to a specific path that maybe suits you better. This is hard to realize when you're going through it but, retrospectively, it was the best thing that happened to me.

What inspired you to pursue a career in life sciences and how do you keep your motivation?

I'm really excited about biology and I have always been drawn to figuring out little details of how things work and how that affects cellular function. Although I experienced challenging times during my career, this motivation to follow curiosity driven research has always remained. Also, it was always important to clarify for myself why I'm doing the work that I’m doing and to take some moments to realign my interests with what I do. Because if you don't, it's a hard job. And if you know for yourself, you have the intrinsic motivation to keep doing it.

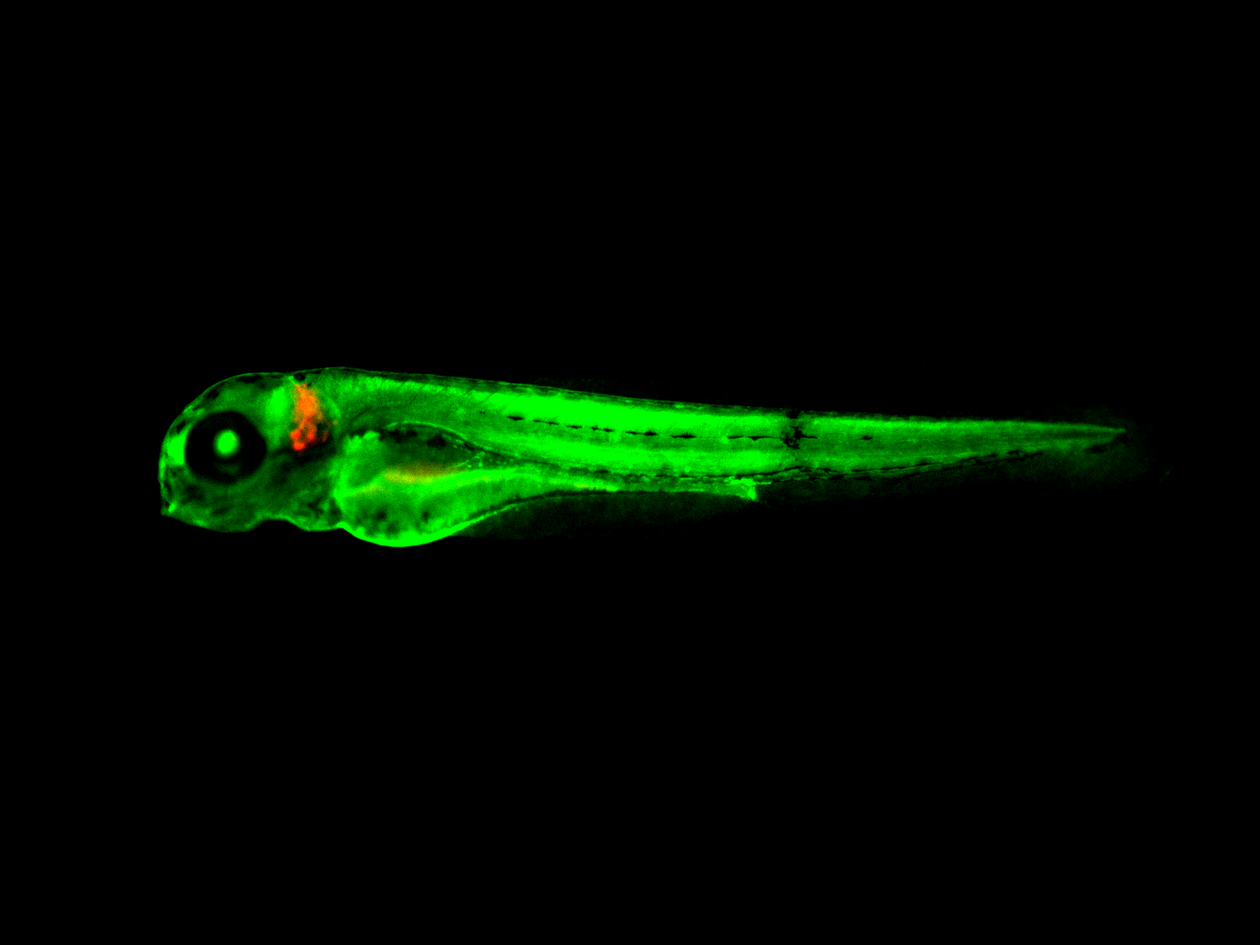

What research are you pursuing now during your postdoc?

I'm really interested in understanding how translation control shapes gene expression as cells acquire distinct fates during zebrafish embryogenesis. I find this biological context very exciting. This is already enough to get me out of bed.

How does a typical day in the lab look like?

I could be either working with the fish, doing experiments in the lab, sitting at the computer analyzing data or writing a manuscript, attending seminars… Every day is very different and that keeps it exciting.

How do you collaborate with other scientists to achieve common goals?

I can give you two examples - interestingly, they're both women. The first example is Júlia Batki, who was also a PhD student at the Vienna BioCenter and now works as a postdoc in Berlin. We have a similar scientific background and work both on the topic of development, but on different aspects of it. The two of us meet every two months to discuss our projects, grant applications, etc. We've been doing this for more than a year now and it's been very rewarding, not just because we give each other critical feedback and advice, but also because I can see her project evolve - that’s fantastic.

The second example is Danny Nedialkova, a professor at the MPI Biochemistry in Munich. I met Danny at a conference where she gave an amazing talk. I approached her afterwards and we started a collaboration that combines our strengths and research interests. Since then, she really took the role of a mentor. She writes reference letters for me, reads my proposals and gives me a lot of feedback. I really feel supported by her.

Do you also see challenges of working in collaborations?

I think that it can be challenging if expectations are not defined. That's something very important. For example, if you need something from them that they're not willing to provide or maybe not so keen on spending time on. But to be honest, I’ve always had a really good experience with collaborations. I tend not to start collaborations just on a whim. There has to be a good reason to collaborate, that benefits everyone involved.

How do you overcome obstacles when conducting scientific research?

Being part of a team where people think in different ways about a problem can be really, really helpful. Also, I'm very lucky that my partner is a scientist, so I very much enjoy discussing my experiments with him and that's also very helpful for troubleshooting and getting advice.

What I've learned is that I need to keep myself healthy and happy outside of the lab to remain motivated at work, too. The body and the mind are not disconnected. I thought before that my body exists only to carry my brain, so that I can think (laughs) - that is completely unreasonable. So now, I keep myself motivated and happy by spending a lot of time in nature. Defining other personal goals that give momentum to my everyday life gives me joy. I also practice Ashtanga yoga. That has changed the way how I deal with challenges. It's not the end of the world if something fails - you take a moment, go do something else, clear your mind and then come back to it. Then sometimes you can fix it in five minutes, other times not, but with patience and perseverance you can work it out.

What advice would you give to young girls who are interested in pursuing a career in life sciences?

It's important to figure out for yourself what motivates you to pursue a PhD and, when you find a supervisor, that you both really clarify expectations so they can be met from both sides. That's really important. A PhD can be very rewarding, but there will be challenges. And I think it's also really important to make sure that you are embedded in a working environment where your approach to work can be aligned with your core values.

Who is a scientist that has recently inspired you, and why?

Lately, I've been awestruck by the papers by Marilyn Kozak. She discovered the Kozak sequence and its importance in regulating translation initiation. Already in the eighties she was so futuristic in how she was approaching science and suggesting experiments that couldn't be done at that time, but that can be done now. I think she's very meticulous and was very brave to challenge science that was conducted by men in a male dominated field.

Do you think the scientific community was different if more women were in leading positions?

It’s not necessarily about having more women, but about allowing women (and people of other genders) with different life paths to be at the top. That would maybe change how things work in science.

What aspects would be better?

The diversity - It's like with any project, if you have different points of view, it brings about different ways of operating. Seeing different people with different family structures or biographies in top positions is motivating and also shows you that it can be done in different ways. Diversity makes it easier for people to find someone to identify with, to reassure them that they too can find their way. It's not just about men or women. It's also about people with different educational backgrounds or origins from a different part of the world.

In your opinion, what would help to make a scientific career more attractive to women?

I think that normalizing parental leave as something that should be equally divided between men and women would probably improve a lot.

What is your wish for girls studying science in school today?

I wish that girls don't feel constrained by the schooling system, that they are free to explore what they want to explore at that moment. Because promoting this exploration is what you need to be(come) a good scientist.

(Interview conducted on March 22, 2023 by V. Herzog)

---

We are sharing profiles of women researchers of the NCCR RNA & Disease as part of the #NCCRWomen campaign. You can find out more about the campaign on YouTube, Twitter or Instagram.

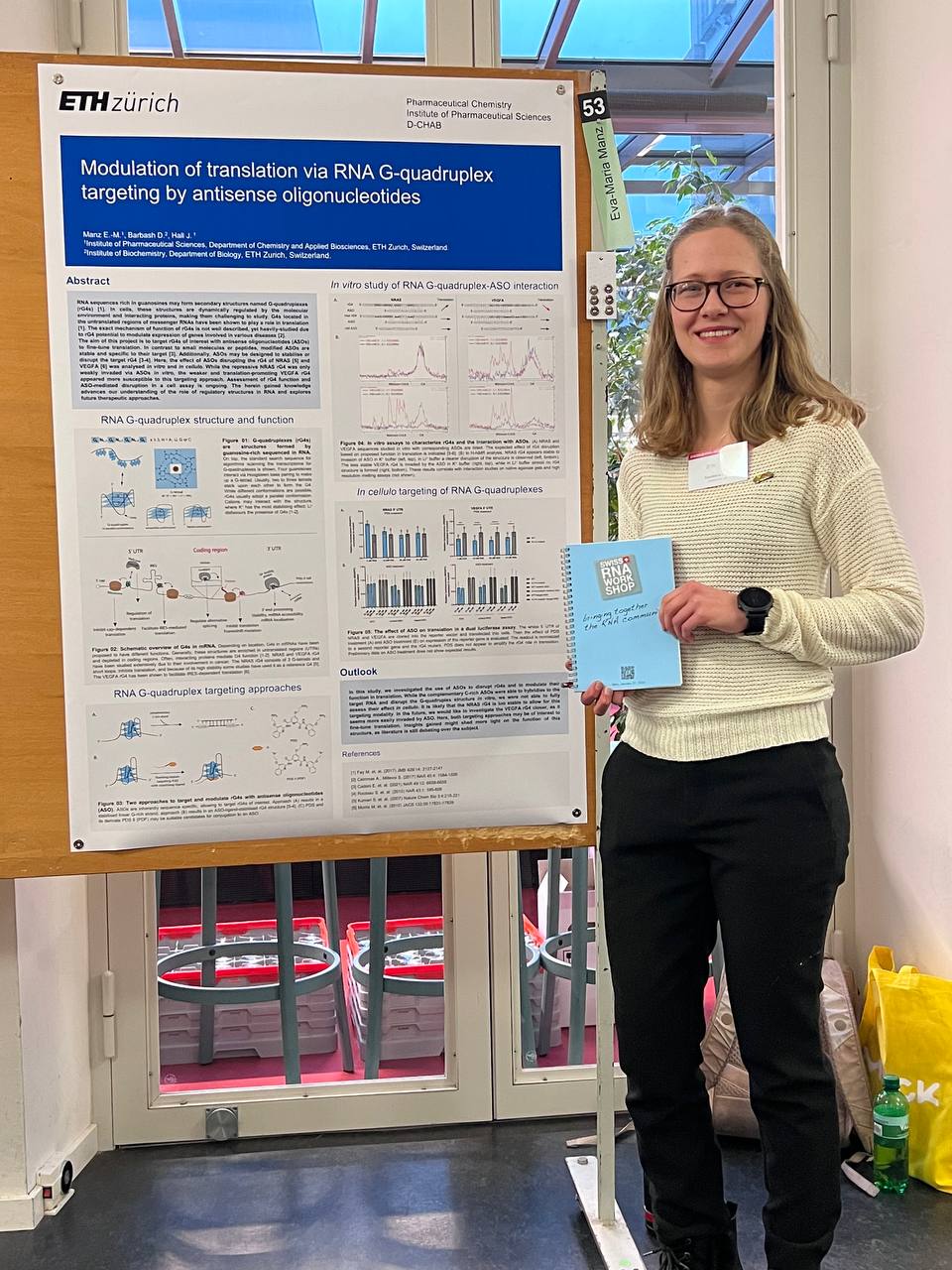

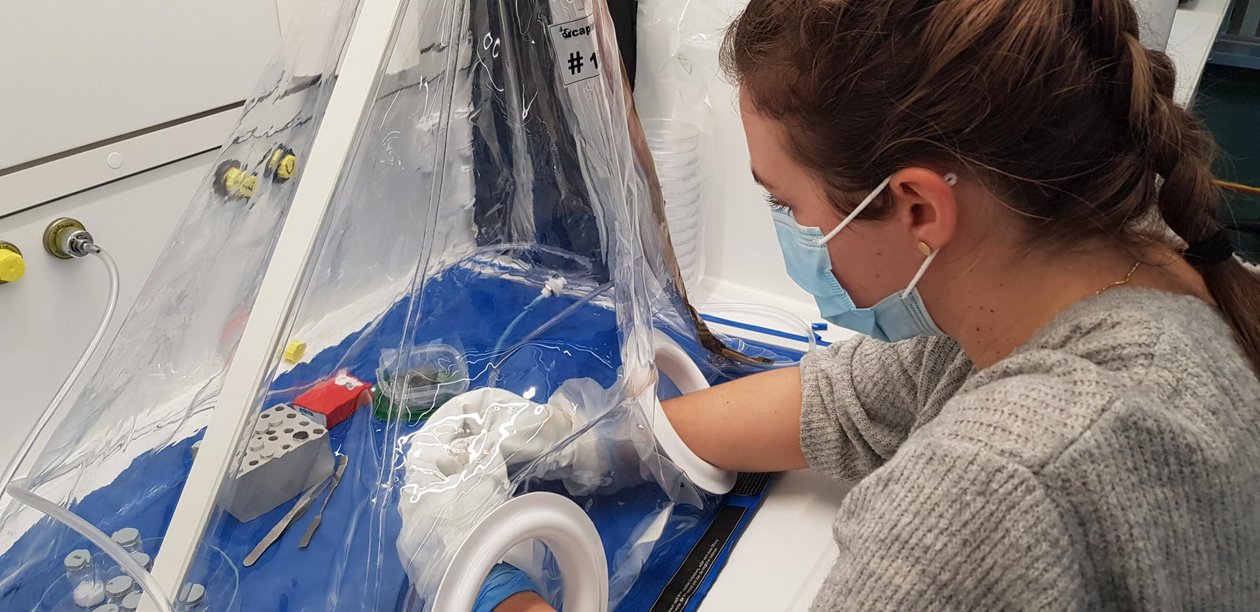

Eva-Maria, born in Tübingen, Germany, pursued her Bachelor’s and Master’s studies in Molecular Health Sciences at the ETH Zurich. As part of her academic journey, she also completed a laboratory internship at Stanford University and an exchange semester at the University of Toronto in Canada. In 2020, she began her doctoral studies in the research group of Jonathan Hall at ETH, where she is investigating oligonucleotide-based treatments for rare diseases such as spinal muscular atrophy and erythropoietic protoporphyria.

Eva-Maria, if you weren't a scientist, what would you be?

I would have to find a job where I am challenged in a similar way to research. I love solving challenging riddles and I am definitely a bit stubborn, so I will not give up easily. Ideally, the job should not be monotonous and include different tasks that can be adapted to best meet the needs.

I also really like baking and I have considered becoming a baker or pastry chef. But maybe some activities should better remain hobbies and not become work.

What inspired you to become a life scientist?

I have always been fascinated by living organisms and the more I learnt about their biology, the more curious I grew. It was a straightforward choice for me to attend a high school specialised in natural sciences and to study Biology at ETH Zurich. An event that really confirmed my passion for research in Biology was the International Summer Science Institute (ISSI) at the Weizmann Institute of science in Israel. Together with 80 international students, I got to spend a month at the institute exploring a project in the lab and the world of research (see photo). To this day, I draw inspiration and passion from this time.

What inspired you to pursue a graduate degree in life sciences and what are some of the most rewarding aspects?

During Biology studies, you are first taught the basic concepts, but as you go on, you are shown the limitations of these concepts and how much we still do not understand. For me, that is where things get interesting. I enjoy analysing a problem and trying to answer a question by designing experiments and discussing the results. The bigger aim is to contribute to humanity’s ever-growing body of knowledge.

I am very grateful to have the opportunity to make a living by simply following my curiosity. Doing research is not easy and experiments do not always succeed. Sometimes they raise more questions than they answer. Yet, it is incredibly rewarding to me when hard work finally pays off and I can draw a conclusion from one of my experiments. An example of this is developing a cellular assay and optimising it to be able to test a set of pharmaceutical compounds. It requires thought, consistent and clean work, and patience.

What does a typical day look like for you? What do you like most and least about it?

A typical day involves some experimentation, including conducting and analysing an experiment, as well as some reflection and planning. Once an experiment is concluded, the results are analysed. Usually, the results inform the next step of the project I am working on. If I am planning a new experiment, I might need to look into existing literature to learn a technique or a colleague may know how to help me. Above all, I need to make sure that I have the materials and tools to perform the next experiment. A considerable amount of time goes into procuring materials and looking after machines in the laboratory. These “house-keeping” tasks are not my favourite, but they need to be done to ensure smooth work on a daily basis.

What is the main question that your research tries to answer?

Broadly speaking, the Hall laboratory studies RNA as a drug and as a drug target. Specifically, we do this by studying RNA in the context of (rare) diseases, such as erythropoietic protoporphyria and spinal muscular atrophy. Here, I try to gain a better understanding of the molecular mechanism of these diseases. This knowledge is the basis of developing treatments or improving already existing ones. My work requires an understanding of biological and pharmacological concepts, as well as mastering techniques in molecular and cellular biology and the chemical synthesis of oligonucleotides.

What fascinates you most about your research topic?

While proteins and DNA have been studied extensively, much less attention was given to RNA. For a long time, it was thought that RNA was only the messenger between DNA and protein. By now we know that there are so many more species of RNA, each with their own characteristics and function(s). I believe that as long as our own genome is not fully functionally annotated, there is more to discover in the world of RNA. And with understanding the human genome comes the possibility to understand, to treat or even cure human diseases. That is what fascinates me, I think that we live in exciting times!

What are some of the most promising areas of research in your field today, and how do you see this field evolving in the future?

While RNA-based therapeutics hold great promise, delivery of these kind of drugs into cells is the biggest issue to solve. Many approaches are being investigated and some are partially successful. But reaching most cells or organs reliably is still a challenge. Only once this delivery problem is solved, will we be able to realise the full potential of RNA as a drug.

How do you collaborate with other scientists and research teams to achieve common goals?

The atmosphere in the lab where I work is collaborative in nature. We do not all work on the same project, but the techniques used and the problems encountered are similar and we help each other.

I have recently started working with another research group as they have a lot of expertise in a technique that I also want to use. Instead of loosing time learning the technique by myself, it makes sense to get advice from experts. In return, my lab group helps the other group with our knowledge and expertise. This way, both groups progress faster, use state-of-the-art procedures and avoid mistakes.

How do you stay motivated and overcome obstacles when conducting scientific research?

It is almost inevitable to encounter obstacles and experience frustrations in scientific research. You have to learn how to deal with these situations. First of all, it is usually helpful to understand the obstacle and discuss it with colleagues. Often, I am not alone with the obstacle, and many fellow researchers have found solutions that may also work for me. And as already mentioned, I like to solve problems, and an obstacle might even hide a new finding.

How do you balance your work as a scientist with your personal life?

It is essential to have projects and hobbies in your free time, especially because I believe that this helps to avoid mental health issues. It is “easy” to dedicate all your time and resources to a scientific project, but it is not necessarily more productive than spending your free time unwinding and doing something else. Latter may even allow you to reflect about your work in a different way and solve a problem or make greater progress by getting a fresh mind. After all, you can always change jobs or projects, but you cannot change your body or mind in the same way, you have to take care of it.

What do you like to do outside the lab?

I have a sweet tooth and I love to bake for others and for myself. Recently, I have also started baking savoury products as bread, bagels etc. Besides baking, I also like to challenge myself physically. About a year ago, a colleague inspired me to train for a triathlon – an endurance sport that involves swimming, biking and running. I am happy to say that with triathlon I have found a sport that I enjoy a lot. I look forward to training every other day!

Where do you find inspiration?

Every day, I find inspiration in other scientists, for example my colleagues or collaborators.

I have recently joined a project called “Wall of Scientists” (https://www.wallofscientists.com/), founded by Enriqueta Vallejo-Yagüe at ETH Zurich. The aim of the project is to showcase scientists who have not received the recognition they truly deserve for their contributions to science. The wall exists physically at ETH Hönggerberg and online. Anyone can contribute to the collection of scientists by suggesting a name or writing a small paragraph about the scientist themselves. It is great to see this project growing and the stories are inspiring.

I also get inspiration from reading books. I am currently reading “RNA – the epicenter of genetic information” by John Mattick, a comprehensive book about the history of RNA biology up to the present day. The book not only highlights the milestones of RNA biology, but is also full of stories of scientists and their contributions that continuously build on each other and advance science. On the side, I am listening to “the code breaker”, a book about Jennifer Doudna and her major scientific contribution – CRISPR-Cas9. I highly recommend this book to anyone interested in life sciences today.

In your opinion, what would help to make a scientific career more attractive to women?

In general, a scientific career is not easy, and the higher up the career ladder you are, the more competition there is for the few positions available. This is only logical and a challenge that both men and women face. It is a challenge that can be overcome if the right and supportive environment is in place. This begins with the application process, where unconscious gender biases need to be addressed. This continues in the personal and scientific development, where role models and mentors are an important support system. And finally, childcare support, if needed.

What would you like to say to your younger self about a scientific career?

It is possible and it is fun! Go one step at the time and enjoy the learning process.

I consider myself very lucky to have a supportive family who encouraged me follow my passion. I do not take it for granted, although I hope for a future where everyone can develop their career as they wish.

What advice would you give to young girls who are interested in pursuing a career in life sciences?

Try to find out what you like to do and what problems fascinate you. Enjoying your studies and work is worth a lot and helps to motivate you in difficult times. Find a mentor in people you admire, be inspired and learn from others.

What is your wish for girls studying science in school today?

That they can fully explore their interests in school and follow their hearts when choosing a career. I hope that they will not encounter any discrimination on their way, but that they will find role models or become a role model themselves. Be courageous and try to change the world for the better.

---

We are sharing profiles of women researchers of the NCCR RNA & Disease as part of the #NCCRWomen campaign. You can find out more about the campaign on YouTube, Twitter or Instagram.

Yeji Kim received her Bachelor’s and PhD degrees from the Korean Advanced Institute of Science and Technology. After her PhD, she wanted to expand her scientific expertise and get to know the working environment abroad. Therefore, she joined the Sebastian Leidel’s group as a postdoc in 2017, when his lab was still located in Münster (Germany). The lab was relocated to the University of Bern in 2019, where she has been working ever since. In her postdoc, she investigates novel microproteins and their function in vertebrate neurodevelopment.

Yeji, what inspired you to become a life scientist?

As a child I had an encyclopedia of wild flowers and trees and I enjoyed remembering them and finding them in nature. People often told me that I should become a life scientist because I was quite good at it. I didn’t even know what it was, but I thought I wanted to be one. I thought that if I became a life scientist, I could go on field trips and observe flowers and trees, which is quite different from what I am doing now.

If you weren't a scientist, what would you be?

I would be a writer or journalist. I have always loved writing and have been good at it. I keep a journal, wrote some scientific columns for the public during my PhD, and have even written short stories. I dream of writing soft science fiction stories where the main character is a scientist.

What does a typical day look like for you? What do you like most and least about it?

On a typical day, I like working in the lab in the morning and doing desk work (analysis, reading, and writing) around 3 pm. My favorite moment in the lab is sitting in front of the microscope and taking immunofluorescent images. I am fascinated by multicolor imaging, and those beautiful images are my favorite data to be included in the figures. Completing my to-do list by checking all the ticks at the end of my day makes me feel satisfied and happy. The thing I like least during my day is preparing presentations. I like presenting itself, but I don’t like making the presentation file since I always feel that I am not good at designing PowerPoint presentations.

What is the main question that your research tries to answer?

My project aims to identify novel coding regions that have not been identified before and characterize the functions of microproteins that are translated from those regions, particularly during vertebrate neurodevelopment. It is like puzzling the missing pieces of knowledge in biological processes.

What fascinates you most about your research topic?

The most fascinating part of my project is the novelty. This field has recently emerged, and there is a lot of room for discovery. You need to be independent and challenge yourself to conduct experiments, interpret data, find different collaborators, and guide your research. I have experienced hardships, but it is also exciting to get through them. Another fascinating thing about my research is that since I am investigating an absolutely unknown protein, my target doesn't have a name yet, and I get to name it!

What are some of the most exciting scientific discoveries that you have been a part of?

The protein that I am currently characterizing does not have a name. It was unknown whether it existed or not, and I am the first person to study this unknown protein. I will be naming this protein when the research is published.

In my PhD project, I worked in collaboration with a hospital to study a rare genetic disorder called citrin deficiency. It occurs rarely, and the majority of patients are East Asian (Korean, Japanese, Chinese), so research on the disease has been limited. I used patient-derived stem cells to study the underlying mechanism of the disease phenotype and was happy that I could contribute to understanding the disease.

How do you stay motivated and overcome obstacles when conducting scientific research?

In my case, overworking has not been the biggest problem. When my research gets stuck, and I have nothing to do but sit in the office and feel useless, it is always a big problem for me and demotivating. I try to encourage myself by fully appreciating every small achievement I make in the lab.

What would you like to say to your younger self about a scientific career?

You don’t have to be obsessed with finishing your PhD early. And, you don’t have to give up other options and ideas (which are branched from science) because you think it will take too long, it will interfere with your PhD project, that you need to focus only on research and nothing else…

What do you like to do outside the lab?

I like going to museums, not only the biggest museums you can visit in Europe, but also smaller local museums to see the pieces of lesser-known artists. During the pandemic I also started baking; I think that baking is a good hobby, especially for scientists. In baking, you get a result if you follow the protocol, not necessarily in the case of an experiment...

Can you describe some of the challenges you have faced as a female scientist, and how did you overcome them?

Sometimes, you face colleagues or seniors who already assume that you don’t prioritize your career because you would get married, have children and take a career break. There were times when I felt I was already excluded from the competition from the beginning. I couldn’t find a specific way to overcome that, but I kept pursuing what I wanted to do and sometimes tried to reveal and promote myself, even on the level that might be a bit aggressive. But I wanted to show that I am serious about what I am doing.

Have you been able to provide mentorship to other young women pursuing careers in life sciences, and what have you learned from these experiences?

I had a few chances to talk to younger women who want to continue studying in a graduate school, and I have one experience I still regret. I was a PhD student and struggled in my research. I told the girl only negative things and challenges of graduate school. Looking back now, it was a hard time for me, but I should not have discouraged her. I keep one thing in my mind: don’t discourage someone’s potential in an excuse of telling “truth” or “reality”.

How important do you think mentorship is in helping young women succeed in the scientific community?

We can be inspired or mentored by scientists of all genders in relation to science, but not always in relation to life. You can learn by taking advice from experienced women in the field and see how they manage their lives at different stages and situations. You can be inspired and prepare your future by implementing what you have learned directly from someone who has already done it.

What advice would you give to young women who are seeking mentorship or looking for role models in their field of interest?

There is no perfect role model who fulfils all aspects perfectly, who you want to copy and learn everything from. But you can always meet and find many women having different strengths and possessing the points that you want to learn and implement.

Do you think the scientific community was different if more women were in leading positions?

Yes, in the end, the scientific community is the same as other communities: they work together. If we had more women in leadership positions, it would give us a more diverse understanding of life and how to deal with it. That would make fewer women leave science.

What is your wish for girls studying science in school today?

If you like science and want to study it, believe in yourself and continue. Don’t listen to anyone who tells you that women are not good at mathematics or science or have a hard time succeeding in STEM fields… I don’t know if there are still people saying this nowadays, but that’s what I was told a lot when I was a schoolgirl.

---

We are sharing profiles of women researchers of the NCCR RNA & Disease as part of the #NCCRWomen campaign. You can find out more about the campaign on YouTube, Twitter or Instagram.

Emanuela Felley-Bosco, an Italian native, obtained her degree in Toxicology from the University of Lausanne in 1986. She embarked on her academic career with three postdoctoral positions, the first at the University of Lausanne, the second at the Swiss Institute on Experimental Cancer Research in Epalinges, and the third at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Maryland, USA. After returning to the University of Lausanne in 1993, she served as a senior researcher and later as a substitute assistant professor. In 2007, she joined the Laboratory of Molecular Oncology at the University Hospital in Zurich, where she worked as a group leader until her retirement in January 2023. Throughout her career, she has conducted translational research in oncology and made seminal contributions to the understanding of tumorigenesis.

What inspired you to become a scientist?

When I was 11 years old, I won a book as a prize for the best student in my school year in Terni, Umbria, Italy (photo 1). It was about the life of a doctor and it gave me the idea to work in the medical field. Later, my father, who had to re-invent his working life in Milano, Lombardy, Italy, was working in the late 60’ in ecology related business, and the idea of “saving the planet” encouraged me to look for a possible later education in water-recycling. Although it doesn’t seem very logical, I nevertheless prepared myself for this by doing classical studies, which in Italy include ancient Greek, Latin, Philosophy and art history. I still don’t regret this choice, although my first university years were quite difficult. During those studies I have been lucky to be encouraged by one of my grandmothers. Because of my good grades in pharmacology and toxicology and the excellence of lectures of one of my professors, I did a PhD in Pharmacology and Toxicology. My mentor allowed me to grow up as independent scientist, and this helped me in the following steps of my career.

What inspired you to pursue a scientific career?

While I was doing my PhD, the person that later became my husband was studying medicine. At the end of my PhD, we needed to accommodate his internships, our familial duties as parents of two children and my wish to continue in research. I was lucky enough to get two postdocs that were compatible with my husband’s heavy clinical duties (photo 2).

My commitment allowed me to receive a fellowship from the Swiss National Science Foundation for a third postdoc at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, USA (photo 3). These experiences allowed me to be integrated in the University of Lausanne, then University of Zurich.

What were the most rewarding aspects of your research?

The most rewarding aspects were on different levels. First, I could do fantastic work where we are allowed to be creative and curious. Second, it allowed me to meet interesting people who share the same passion. Third, the transmission of know-how to younger generations has been a joy (photo 4). And fourth, this career allows meeting people from different cultures, which is always an enriching experience (photo 5).

If you weren't a scientist, what would you be?

I would be an artist: same freedom, same problems.

What did a typical day look like for you? What did you like most and least?

During a typical day there is the need to equilibrate the time between supervision of the team, keeping up with knowledge in the field, and administrative tasks. My preferred time is team supervision, since this is the direct product of the creative work. The worst is time spent in administrative tasks, especially when there is no support by the infrastructure.

What is the main question that your research tried to answer?

My research has aimed at elucidating various aspects of the relationship between chronic inflammation and cancer with a later focus on mesothelioma, which is a rare cancer, mostly occurring in individuals who have been exposed to asbestos. Not every person exposed develops this terrible cancer and we addressed several mechanisms including genetic predisposition, transcriptome alterations and implication of the immune system.

What fascinates you most about your research topic?

Our most recent work, in which we addressed the mechanism of mesothelioma development, revealed that we should pay more attention to RNA, especially to what has been defined as “the dark matter” - the genome, which has been known to be transcribed for several years, but which is not well characterized. Dr. Mattick, together with Paulo Amaral, describes well in his book “RNA: the epicenter of genetic information”, published in 2023, how we should change our dogmatic view, which is centered mostly on proteins, based on the knowledge we have acquired from the bacterial world.

What are some of the most exciting scientific discoveries that you have been a part of?

I had the privilege to work on different exciting projects, including the development of a method to detect low frequency mutations in tumor suppressor TP53, which are induced, for example, by endogenous production of reactive oxygen species; the functional characterization of an important polymorphism of TP53; and, more recently, RNA editing during the development of mesothelioma.

How did you collaborate with other scientists and research teams to achieve common goals?

Since I started as an independent scientist in 1994, I cherished collaborations, in which common goals are achieved through commitment and good communication.

What have been some of the benefits and challenges of working in a collaborative environment?

Working in a collaborative environment has mostly benefits: constructive exchange about methods and approaches, discussion about results and analysis strategies. The challenge, especially when working in multiple teams, is keeping everyone posted. I addressed this issue by compiling extensive minutes of exchange.

How did you balance your work as a scientist with your personal life?

When I started, not much existed to balance family and work life. Our strategy was simple: Reduce social life to what was compatible with family life.

Where do you find inspiration?

Inspiration for ideas, I found at night, when I could not sleep, or during outdoor activities. I found inspiration to fight to continue my work through people in my surroundings.

What do you like to do outside the lab?

I like doing Yoga, swimming, hiking in the mountains (photo 6), painting and drawing, taking care of my three grandchildren, or taking care of our vineyard (photo 7).

Can you describe some of the challenges you have faced as a female scientist, and how did you overcome them?

During my PhD, we had our first child. I heard people defining me in ways that are forbidden today. Later, I experienced a similar kind of discrimination twice. It was only because of one of my defects, stubbornness, which can be a quality in some occasions, I pursued my scientific career.

What advice would you give to young girls who are interested in pursuing a scientific career?

It is the same advice I gave my students: “Life is not a straight line, there are ups and downs and it is the same in science. As a woman, one is “formatted” for anticipation and this helps.”. So, if you have the passion, go for it.

In your opinion, what would help to make a scientific career more attractive to women?

Young people today have concerns that we did not have when I started. We lived more in the present and believed that our passion and commitment would take care of the future. To re-boot that feeling, nurturing female dedicated PhD students and postdoc may help.

What role do you see mentorship playing in the scientific community?

Mentorship is crucial. I have benefitted from it and tried my best to do the same for younger people.

Who has been the biggest role model or mentor in your scientific career, and how have they influenced your work?

I have already mentioned my PhD advisor and how he influenced my work. Later, my boss at the National Cancer Institute USA allowed me to gain enough confidence in my work so that I became ready to be independent. Complete freedom in research was granted to me later when I started working in Zurich. These three persons share strong ethics and, in their own manner, are committed to common wealth.

What advice would you give to young women who are seeking mentorship or looking for role models in their field of interest?

Mentorship as well as role models can be found in men and women scientists who seek to really improve the scientific career of women.

Have you been able to provide mentorship or support to other young women pursuing careers in life sciences?

Mentoring other scientists pursuing careers in life sciences was a manner to express my gratitude and contribute to common wealth. I wish common wealth would be more considered as scope in life by world citizens.

What are some of the biggest challenges facing the scientific community today, and how can we address these challenges?

The pace at which new knowledge is acquired is too fast and more time should be dedicated to thinking. It is not clear how this can be achieved.

What would you like to say to your younger self about a scientific career?

A scientific career is a dedication, includes joys and sacrifices, but it is fun to learn.

---

We are sharing profiles of women researchers of the NCCR RNA & Disease as part of the #NCCRWomen campaign. You can find out more about the campaign on YouTube, Twitter or Instagram.

Vera is originally from a small village in the canton of Solothurn. She gained her bachelor’s degree in Molecular Bioanalytics in the Molecular Life Sciences program at the University of Applied Sciences of Northwestern Switzerland FHNW and then switched to the University of Zurich to pursue the master’s degree in Virology. While being enrolled in the Masters, she also worked part-time as a scientific assistant at the Institute of Pharmatechnology at the FHNW. During her studies she discovered her interest in Bioinformatics and Programming and so she decided to also pursue a Minor degree in Bioinformatics. She has just completed her master’s thesis entitled “Comparison of MERS-CoV infection in human and camelid primary airway epithelial cells with single-cell resolution” under the supervision of Volker Thiel at the University of Bern.

What did a typical day look like when you were working on your Master thesis’ project?

During my Master thesis project, my typical day varied depending on what phase I was in. Typically, I started the day by taking some time for myself: A short walk, going to the gym or reading. Working from home made that easier because you could use the time before work differently. I often started work with planning the tasks of the day and then start with the harder tasks, either coding or writing. I wrote a lot of code during my project, so I sometimes spent multiple days only doing that. On days when I went to the lab, I joined seminars, had discussions with colleagues and my supervisors.

What is the main question that your research tries to answer?

The main question my Master project tried to answer is why camels react so differently to MERS-Coronavirus compared to humans. Humans can get very sick from MERS, but camels only have a mild disease, often early in their life. Using computational tools, we can analyze large amounts of data of infected cells and find patterns in the way the cells reacts to the virus. By comparing patterns of humans and camels, we hope to find certain genes or pathways in the cells, that are responsible for the strong disease. This knowledge could then help in developing medication or vaccination to prevent people from dying from MERS.

How do you stay motivated and overcome obstacles when conducting scientific research?

I realized that the best way to stay motivated while conducting scientific research is to set time limits and take breaks. This break can be grabbing a coffee, talking with friends, or watching a comforting series over the weekend. When you know that a hard situation is temporary, it is much easier to power through or finish that one annoying task. With obstacles you cannot easily overcome, it is also okay to ask for help or mental support.

What would you like to say to your younger self about a scientific career?

Don’t be scared, everyone was new and inexperienced once. I was always worried to be behind in mathematical and chemical knowledge, which made me hesitate to pursue science. Luckily, my curiosity prevailed.

How do you balance your work as a scientist with your personal life, and what strategies have you found to be effective for maintaining “work-life balance”?

To be honest, I sometimes balance it very poorly. It is not always easy to find the perfect balance, because there is always another thing you should do, or you don’t have much energy left to do something after work. During these times, I am very thankful for my partner and family who take me away from my computer. Even doing something little for myself helps me to get back on track. I am still developing effective strategies, but setting boundaries and having hobbies that excite me helps a lot.

What do you like to do outside the lab?

After finishing my undergraduate studies, during which I neglected hobbies altogether, I’ve been spending much time trying new activities. I love to cook, especially when I have time to try elaborate recipes, like making pasta from scratch. During the summer months, I like to go hiking and climbing and since we live in Olten, we swim in the Aare whenever possible. It’s great to have smaller hobbies that you can do on a weeknight and bigger ones that you do occasionally.

Can you describe some of the challenges you have faced as a female scientist, and how did you overcome them?

I think the biggest challenges I have faced came from within myself, rather than from the scientific community. I think many girls are not encouraged enough to be assertive or are shown that they have to be perfect to stand a chance. This can make it difficult to start a scientific career, especially, when there is competition and you work yourself close to a burn-out. I failed multiple times to ask for help because I didn’t want to be perceived as weak or stupid. And the perfectionism I thought was necessary to succeed, held me back, because it’s an unattainable goal. I don’t think this is inherent to women, but I think it’s a pattern that we can tackle from within ourselves. Learning to try new things, without worrying about achieving perfection can be a challenge, but it is a mindset that will ultimately be beneficial in the long run.

Who has been the biggest role model or mentor in your scientific career, and how have they influenced your work?

I have met many different people throughout my career that I later identified as role models. The first person was undoubtedly my biology teacher. She was the first to introduce me to scientific work and sparked my interest in biology. Later, I also had wonderful male supervisors, who had pivotal roles in my studies and career, by primarily believing in me and giving me confidence. I think its enriching to have male and female role models, as it shows you diverse ways in which scientists can teach, research and lead.

What advice would you give to young women who are seeking mentorship or looking for role models in their field of interest?

I did not actively search for a mentor; however, it can be pivotal to actively engage with supervisors or teachers that want you to grow as a scientist. Mentors can be found in many places, and the more you engage with them, the more they will teach you. My advice would be to surround yourself with people that love their research, are willing to teach and are good role models for the kind of life you want to live. Mentors can be more experienced supervisors, but also your peers.

What is your wish for girls studying science in school today?

It is important to keep in mind that no scientist is a perfect human being, so you don’t have to be either. It is possible to pursue science while staying empathic, fair, and curious and doing so can contribute to making academia a better place.

---

We are sharing profiles of women researchers of the NCCR RNA & Disease as part of the #NCCRWomen campaign. You can find out more about the campaign on YouTube, Twitter or Instagram.

Portrait of Valeriia Volodkina, PhD student in the Meister Group, Institute of Cell Biology, University of Bern

Portrait of Magdalini Polymenidou, Professor at the Department of Quantitative Biomedicine, University of Zurich

Portrait of Jasmin van den Heuvel (postdoc), Kerstin Dörner (PhD student), Claudia Gafko (PhD student), Chiara Ruggeri (PhD student) from the Kutay Group, Institute of Biochemistry, ETH Zurich

Portrait of Nancy Carullo, Postdoc from the Mansuy Group, Brain Research Institute (University of Zurich) & Institute for Neuroscience (ETH Zurich)

Portrait of Stefanie Jonas, Professor at the Department of Biology, ETH Zurich